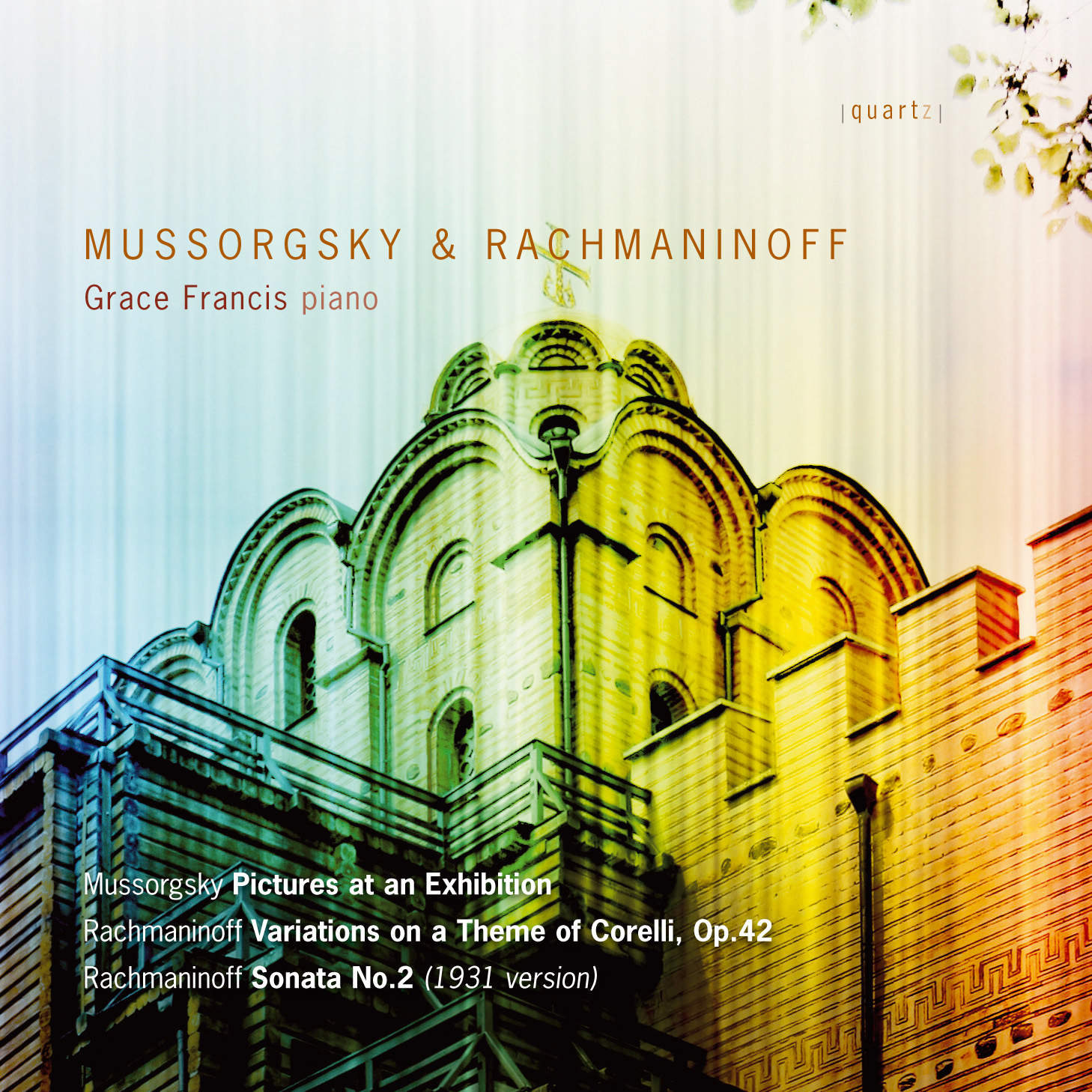

Mussorgsky & Rachmaninoff

£5.99 – £11.99

Mussorgsky

Pictures at an Exhibition

Rachmaninoff

Variations on a Theme of Corelli, Op. 42

Sonata No. 2 (1931 version)

“This exceptionally gifted young player…” —Musical Opinion

About This Recording

Whereas today the notion of a highly talented pianist coming from Russia might not seem to be the unsurprising event of forty or fifty years ago, when the mid-20th century pantheon of Soviet pianists – Richter, Gilels, Berman, Ashkenazy and Gavrilov among them – appeared as heirs to the earlier examples of Horowitz, Moisewitsch, Brailowsky, and others, one might pause and consider how that tradition arose in the first place. The founder of the Russian school of piano playing was Anton Rubinstein who in 1862, encouraged by the Russian royal family, established the first Russian music college in St Petersburg, a seat of learning to rival those in German-speaking Europe. Rubinstein was a great musician – pianist, composer, conductor and pedagogue – and was able to attract outstanding colleagues to join the teaching faculty of the new Conservatoire. Yet whilst, on the one hand, this development marked a great step forward in art music in Russia, on the other the German Rubinstein’s engagement of so many foreign professors led to a schismatic reaction on the part of several greatly gifted indigenous composers. Misplaced anti-Semitism also played its part – Rubinstein was thought to be Jewish (which he wasn’t) – and the members of a group of young nationalist composers who came to be known as ‘The Five’ (or ‘The Mighty Handful’ – Balakirev, Borodin, Mussorgsky, Cui and Rimsky-Korsakov) all had full-time jobs which debarred them from giving due time to musical study or practice. By 1862, the ages of ‘The Five’ ranged from 18 to 28, and although Tchaikovsky, for example, was their contemporary (he was then 22) and was a civil servant, he was more respectful of Rubinstein and of his methods, and became one of the Conservatoire’s first pupils. Rubinstein’s brother Nicholas was to found a rival Conservatoire in Moscow a few years later.

Another route into music was through the Army; in 1856, at the age of 17, Mussorgsky, scion of a wealthy family, had joined the Preobajensky Guards as an officer cadet. In the Army, Mussorgsky met the 23-year-old military doctor Alexander Borodin, attached to the same barracks, and their mutual interest in music developed into a close friendship.

Borodin described his younger colleague as ‘a dapper, aristocratic little cadet officer, rather affected and foppish, who would sit at the piano and play excerpts from Verdi’s operas.’ The life of a Guards officer was given over, socially, to drinking, gambling and almost all other forms of licentiousness. The seed of the chronic alcoholism, which claimed Mussorgsky’s life at the age of 42 in 1883, was sown here. Borodin also described Mussorgsky as a somewhat weak character, an impression certainly not imparted by his music.

Mussorgsky resigned his commission soon afterwards, devoting himself to music, but his dependence on alcohol weakened his resolve, and he found it difficult to apply himself to composition as fully as his great gifts demanded. He sought the company of other musicians and artists, and when the Russian painter and architect Viktor Hartmann died suddenly in Moscow on July 23rd 1873 his death affected Mussorgsky (one of his close friends – not of long standing, for they had met but a short time before) deeply. A year after Hartmann’s death, Mussorgsky paid the artist a tribute in music on the occasion of a posthumous exhibition of the painter’s work. This took the form of a suite for solo piano, Pictures at an Exhibition, each movement taking as its inspiration one of Hartmann’s paintings, occasionally linked by a ‘Promenade’, which is possibly a selfportrait (albeit not an extensive one) of the composer, strolling through the gallery and looking at each picture in turn. The ‘Promenade’ theme has the aspect of Russian liturgical chant and is in irregular metre. Hartmann’s death indirectly inspired another work, begun at about the same time but completed in 1875, the Songs and Dances of Death – a song-cycle that quotes directly from ‘Pictures’.

Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, despite being in many movements, has an underlying sense of forward-projection that lends a degree of continuity to the score as the music approaches the magnificence of the final Great Gate of Kiev. Notwithstanding the inherent ‘Russian’ nature of the music, it also (perhaps inevitably) contains the seeds of the dawning of musical Impressionism. By the end of the 1870s, Debussy was to Nadezhda von Meck. The composer-pianists of the later generations – notably Scriabin and Rachmaninoff, who had both studied at Nikolai Rubinstein’s Moscow Conservatoire – unlike many of ‘The Five’, almost invariably wrote sonatas and large scale works for the piano as a matter of course, perhaps taking the example of Tchaikovsky as their model. Rachmaninoff produced two large-scale solo sonatas, against the ten shorter examples by Scriabin. The first of these sonatas appeared in 1907, same year as Rachmaninoff was composing his Second Symphony; he completed the Second Sonata in 1913 while working on his choral symphony, The Bells, which was premiered on December 13 that year, conducted by the composer himself.

Three days later, in Moscow, Rachmaninoff gave the premiere of the new Sonata, which begins with a peremptory, displosive gesture: all is caprice, teeming with life, until at last a theme appears, quietly worming around its pivotal note. This opening material is counterstated, leading to a new idea, a descending scalic motif heralding the brief development. The first movement ends with an unanswered question and the second begins with another, a sequential descending idea, worlds away from the bustle of the first movement. It is a quiet Summer’s day in Southern Russia, the butterflies gently fluttering amongst the rich colours of the motionless roses and lilacs in full bloom, the grass warmed with haze, the earth full, yet not damp underfoot. At the point in this movement where one expects the reprise of the Lento, the music gently muses on the two main themes of the first movement. The coda is Schumannesque, if Mendelssohnian in form, as a brief Intermezzo before the finale banishes the reverie with a coruscating display of energy – structurally not unlike a Chopin Scherzo, the coda fulfilling the function of a traditional recapitulation, brilliant in the extreme, the major mode triumphant. A little over 16 years later, having left Russia in the wake of the 1917 Revolution and largely adopting the life of a touring virtuoso, Rachmaninoff performed Chopin’s B flat minor Sonata in February 1930 at Carnegie Hall, which he recorded a few days later. Inthe Summer of the following year, he published a revised version of his own Second Sonata (in the same key as Chopin’s), tightening the structure and considerably thinning the texture, claiming that in the first version: ‘So many voices are moving simultaneously, and it is too long. Chopin’s Sonata lasts nineteen minutes, and all has been said.’

Concurrently with making the Sonata’s new version, Rachmaninoff completed his last original work for solo piano, the Variations on a Theme of Corelli, Op.42, dated 19 June, 1931. The theme on which the Variations are based was shown to Rachmaninoff by Fritz Kreisler, to whom he dedicated the work and with whom in 1928 he had recorded sonatas by Beethoven, Grieg and Schubert but the theme is not by Corelli, being an anonymous tune known as ‘La Follia’, used by Corelli in a piece of his own. Rachmaninoff’s Corelli Variations are in the composer’s favourite key, D minor. The first thirteen variations share this key; wide-ranging and laconic, and containing elements of Passacaglia, they culminate in a cadenza which falls to D flat major. As in the later Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini, this key is the emotional heart of the work, revealed in adjacent nocturnal variations. D minor returns, Allegro vivace, in four variations before the coda which build to a blaze of fire. The penultimate variation opens as if the number of bars is to be very formal when, suddenly, Rachmaninoff extends this in a tremendous passage of howling descending chromatic scales, largely quoting the ‘Chorus of Doomed Spirits’ from his opera Francesca da Rimini (1905). It seems as if there is no hope until the final variation, where Rachmaninoff shows some light at the end of the tunnel, allowing the right hand to soar into a beautiful melody over several octaves. With this brief yet confident gesture, Rachmaninoff’s original compositions for his own instrument come to an end.

Robert Matthew-Walker © 2012

Track Listing

-

Modest Mussorgsky

- Pictures at an Exhibition (i) Promenade

- Pictures at an Exhibition (ii) Gnomus

- Pictures at an Exhibition (iii) Promenade

- Pictures at an Exhibition (iv) Il Vecchio Castello

- Pictures at an Exhibition (v) Promenade

- Pictures at an Exhibition (vi) Tuileries

- Pictures at an Exhibition (vii) Bydlo

- Pictures at an Exhibition (viii) Promenade

- Pictures at an Exhibition (ix) The Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks

- Pictures at an Exhibition (x) Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle

- Pictures at an Exhibition (xi) Promenade

- Pictures at an Exhibition (xii) The Marketplace at Limoges

- Pictures at an Exhibition (xiii) Catacombs

- Pictures at an Exhibition (xiv) Con mortuis in lingua mortua

- Pictures at an Exhibition (xv) The Hut on Fowl's Legs (Baba Yaga)

- Pictures at an Exhibition (xvi) The Great Gate of Kiev Sergei Rachmaninov

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Theme - Andante

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. I - Poco piu mosso

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. II - L'istesso tempo

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. III - Tempi di Menuetto

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. IV - Andante

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. V - Allegro (ma non tanto)

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. VI - L'istesso tempo

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. VII - Vivace

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. VIII - Adagio misterioso

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. IX - Un poco piu mosso

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. X - Allegro scherzando

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XI - Allegro vivace

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XII - L'istesso tempo

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XIII - Agitato

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Intermezzo

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XIV - Andante (come prima)

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XV - L'istesso tempo

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XVI - Allegro vivace

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XVII - Meno mosso

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XVIII - Allegro con brio

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XIX - Piu mosso - Agitato

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli - Var. XX - Piu mosso - Coda - Andante

- Sonata No 2 in B flat minor Op. 36 (i) Allegro agitato

- Sonata No 2 in B flat minor Op. 36 (ii) Non allegro - Lento

- Sonata No 2 in B flat minor Op. 36 (iii) Allegro molto